Top high school programs around the country gain, lose players when their coaching fathers get new jobs.

When the Indianapolis Colts fired head coach Jim Caldwell in January, one of the first questions that

Carmel (Ind.) head coach Kevin Wright had was: Who would coach the running backs?

The

question was not born out of a concern for the Colts' ground game,

which finished 26th in the league last season. Rather, Wright, who

guided Carmel to a Class 5A state title in 2011, wondered what would

happen to Colts running backs coach Kevin Walker, and more specifically,

his son Jalen.

Kevin Wright, Carmel

File photo by Warren Robison

The younger Walker moved into Carmel's school

district when his father left his position with the University of

Pittsburgh last winter to take a job with the Colts under Caldwell. He

dominated middle school football and quickly established himself as one

of the top young players in the area.

With his father's job

status in flux, Wright wondered if the seventh-grade phenom would ever

suit up for Carmel in a varsity football game.

"His son was an

impact player right away. Led his middle school team to a title," Wright

said. "When everything went down with the Colts, we were hoping Coach

Walker would keep his job."

Family mattersOften

lost in the media deluge that accompanies high-profile coaching changes

is the reality that many coaches have families that are affected, both

positively and negatively, in the transition.

It can be especially difficult for children, according to Wright.

"It's

a little unsettling for kids," he said. "Sometimes we forget when we

look at coach moves that there are young kids that are involved."

Wright should know. He left a position at powerhouse

Warren Central (Indianapolis) to become the head coach and athletic director at

Union (Tulsa, Okla.). Essentially, he left one high school national power for another one nearly 700 miles away.

That

type of move is nearly unprecedented on the prep level. However, Wright

said that the uncertainty of the future - and the toll that can take on

a family - is not uncommon for high school coaches, even highly

successful ones.

"Coaching is tough when you have a family. We

have a kids, and we talk about that all the time," Wright said. "My

family has moved several times."

Robert Weiner, Plant

File photo by Gray Quetti

head coach Robert Weiner, who has coached the sons of several prominent

coaches, said it's something that the kids become accustomed to.

"For

some of them, it is a little bit hard," Weiner said, mentioning that

many miss the friends they left behind. "It's like an army brat kid.

That's what it's like to be someone in college or pro football. That's

the nature of the business. They understand that."

According to new Plant defensive back

Tristan Cooper, it's something that people outside of the coaching community tend to overlook.

"I don't think too many people pay attention to it. I know I do," said

Cooper, who moved to Tampa from Baton Rouge after his father left LSU to

join the Bucs. "For example, when LSU hired Coach Kragthorpe, the first

question the coaches' kids ask their dad is does he have kids, how old

are his kids. Coaches' kids have that kind of bond."

Best of both worldsCoaches seek out a good fit for their child both athletically and academically, according to Wright.

"I

think that's probably what coaches and their families look for when

they have to look at making a move," he said, "schools with good

athletics and good academics."

For

Austin Roberts, who is set to transfer this spring from Plant to Carmel, the process began with a simple internet search.

"My brother Avery and I just started Googling schools, seeing their

(academic) ratings, how good their football team's record was, the

coach's phone number," he said. "I have a sister in middle school. My dad wanted to find a good school district. It was a full family effort."

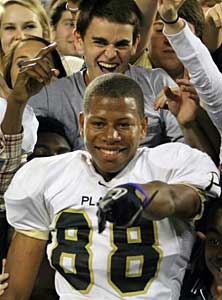

Trey Holtz, Plant

File photo by Stuart Browning

Often,

relocating to a district with a top public school with a successful

sports program is the answer. Weiner, whose rosters have included Eric

Dungy (son of former Buccaneers and Colts coach Tony) and Trey Holtz

(son of USF head coach Skip Holtz), said that it's simply a case of

parents wanting what's best for their children.

"They like to

have their kids at really, really good places. And I like to think our

place is a really, really good place," Weiner said.

Other times,

the son of a coach might land at a top private school. That was the

case when Bobby Petrino became the head coach at Louisville in 2003. He

enrolled his sons Nick and Bobby Jr. at

Trinity (Louisville, Ky.), a Catholic all-boys school with the area's most successful football program.

Greg Schiano transferred his oldest son, Joe, from Immaculata, a co-ed Catholic school not far from Rutgers, to

Berkeley Prep (Tampa, Fla.), an elite private school in Tampa, after leaving the Scarlet Knights to become head coach of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers.

In one of the most high-profile transfer stories of the offseason, freshman phenom

Kahlil McKenzie announced that he expected to transfer from

Southwest (Green Bay, Wis.) to

De La Salle (Concord, Calif.) after his sophomore season. McKenzie's father Reggie left the Packers to take the GM job with the Oakland Raiders.

De La Salle, which has yet to hear from McKenzie or his family, stands to benefit greatly.

Even if it may be transient, what these players bring to high school teams is often more than combine numbers can quantify.

Coaches on the fieldWeiner

still remembers the moment when Eric Dungy truly arrived in Plant's

offense. When he transferred from Park Tudor to the Florida powerhouse,

he was far from the player that signed with Oregon in 2010.

"Eric

was like his father," Weiner said. "He was not a great, great high

school player. He was a late bloomer. Eric was really not a great player

when he came to us."

However, he spent every possible minute in Weiner's office, dissecting film and absorbing everything he could.

"He drank in the game," Weiner said.

When

Dungy had earned time at receiver (he also played defensive back), his

first play displayed his football acumen. He caught a pass, was

seemingly taken down but never hit the ground. Without any hesitation,

he got up and kept running for a touchdown.

"That's just a guy who's watched and talked football with his dad," Weiner said. "You don't teach that."

Weiner

said that, though it's hard to calculate, the intangible of being a

coach's son is very valuable to a high school program.

"Across

the board, if you have someone in that situation, you just know the kid

has been around football all his life. You know you have a football, gym

rat mentality. That's just something you can't replace," he said.

Weiner

pointed to Trey Holtz, who was invaluable to Plant last season. After

losing out on the starting quarterback battle, Holtz served as the

team's holder and rugby punter, making correct reads and booting several

punts inside the 5-yard line in the playoffs.

"You get a lot of benefits with a kid like that, even if he's not the No. 1 guy scoring touchdowns."

Eric Dungy contributed greatly to the Plant football program. Tony Dungy, by extension, also left his mark.

File photo by Gray Quetti

{PAGEBREAK}

Revolving doorAs quickly as a coach's son can show up on campus, one can depart just as swiftly.

Austin Roberts, Plant

Photo by Bill Ward/The Tampa Tribune

Plant

learned that lesson in recent weeks. Roberts, who Weiner believes will

be a Top 10 national recruit as a senior, is preparing to transfer from

Plant to Carmel (He also considered Cathedral and Noblesville.). His

father Alfredo was not retained by Greg Schiano and landed a job with

the Colts in February.

Roberts will be difficult to replace.

Weiner said it was painful to read out his 40-yard dash times - 4.51 and

4.52 - on his notoriously slow hand time, knowing Roberts likely would

never suit up for Plant again.

"Those times aren't for me. They're for someone else," he joked.

Wright,

who could only confirm that Alfredo and his brother Avery did the

school's shadow program for prospective students, said he has read

articles in the paper about Roberts transferring there, but could not

comment any further since he has yet to enroll in the school.

"From what I've read, they're coming," he said.

Meanwhile,

University Lab's (Baton Rouge, La.) loss is Plant's gain. When Ron Cooper left LSU to join Schiano's staff with the Buccaneers, his son Tristan enrolled at Plant.

There's

also the chance that Ron Cooper, who coached the likes of Patrick

Peterson, Morris Claiborne and Tyrann Mathieu, may offer a few pointers

at Plant's practices, similar to what Alfredo Roberts did during the NFL

lockout, another perk to having a coach's son in the program.

"He

just wanted to coach. My receivers coach was out of town for our spring

game and Alfredo was our lone coach for that position. It was so cool,"

Weiner said.

What the future holdsFor now, Kevin Wright is in the clear.

The

Colts' new head coach, Chuck Pagano, held on to running backs coach

Kevin Walker, meaning his son Jalen, the jewel of the Carmel football

middle school program, is not going anywhere - for now.

"We're hoping he'll be here all the way through his high school years," he said.

If not, some school just like Carmel, but located in the shadows of some different NFL stadium, will be the beneficiary.