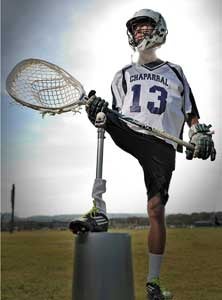

Sophomore lacrosse goalie keeps his posture straight, head up and vision focused on all things possible.

Chandler Smith has worn an above-the-knee prosthetic since he was 1, but it hasn't deterred him from any athletic venture.

Photo by Louis Lopez

TEMECULA, Calif. – Like a guard at Buckingham Palace, Chandler Smith stands tall and stoic, protecting his own sacred ground: The crease of his team’s junior varsity lacrosse goal.

The eyes of the Chaparral (Temecula, Calif.) sophomore pierce through a large protective mask. His heavily padded gloves wield a 50-inch alloy stick, with the right hand gripped tightly at the top near the netting and the left squeezing three-quarters down.

When action flurries at the other end, he twirls the rod like a golfer spinning a club between shots. When opponents attack, Smith crouches slightly, moves his feet and extends the stick. He looks fierce, like a middle linebacker waiting for a ballcarrier to break through the line.

This is Smith’s domain, his home away from home.

“From the

moment I played lacrosse I fell in love with it,” he said. “I love all

sports, but there’s something about lacrosse that really gets my

adrenaline going.

“I don’t know. I just think I was born to be an athlete.”

That’s quite a statement and perspective from a 16-year-old born with a rare birth defect that left him without a right leg.

Smith

came into the world with proximal femoral focal deficiency, a

non-hereditary bone deficiency that caused absence of a tibia, deformity

of the right foot and underdevelopment of his femur. His leg

was amputated at 18 months, when he received his first above-the-knee

titanium prosthetic. He’s been fitted for new ones almost annually ever

since.

Along the way, supported by encouraging parents Richard and

Jennifer Smith, and sole sibling 14-year-old sister Courtney Smith, plus a large cast of teammates in various sports, Chandler hasn’t missed

an athletic step.

Video shot by Craig Johnson

He played T-Ball at age 5, soccer at 6 and golf soon after. He tried basketball in the eighth grade and wrestled last year, but gave it up because it conflicted with lacrosse, a sport he picked up the year before.

“I have to play a sport,” he said. “I feel like I’m not doing anything if I’m not doing one. I need to be active.

“I just don’t want to be the one kid sitting on the couch all day playing video games. I want to be out here running, throwing, catching, sprinting, jumping. All that.”

He does all that and a lot more, said Chaparral first-year junior varsity coach Tim Mann, a former college lacrosse goalie. Chandler isn’t by any means the Pumas' top player – he’s still learning the game and splits time at goalie – but he adds an element of spirit, hustle and a competitive edge that is immeasurable.

“He raises everything up for this team,” he said. “They look at the joy he brings to the game. The seriousness he brings to the game. Just his overall determination to be better, regardless of what’s going on in his life at the time. The team feeds off that a lot.”

Even one of the top players on the varsity team.

Sophomore Michael Kay has been playing the game six years and his dad Brent is the varsity head coach.

“The kid’s got heart, man,” Kay said. “I’ve never seen someone with so little give and do so much. I mean when the ball is loose, he can really run. He really gets going.

“I don’t know. When I watch him I just feel real gifted and real thankful just being here. I feel real whole. Real solid. Real lucky.”

Remarkably, so does Chandler. {PAGEBREAK}Why me?

Smith has been strapping on a lacrosse helmet for just two years.

Photo by Louis Lopez

Chandler doesn’t talk much about living with a disability. That’s because, “I don’t really know any different,” he said.

There are inconveniences to be sure, like having to remove his prosthetic every day to sleep and shower. Or making regular 90-minute trips to Shriners Hospital for Children in Los Angeles to get fitted for a new prosthetic.

But he’s certainly not complaining about that. Insurance covers only $1,500 a year for an above-the-knee titanium prosthetic that costs more than $30,000.

“They consider it durable medical equipment like a wheelchair or crutches,” Richard Smith said. “Ridiculous.”

Shriners, known as "The World's Greatest Philanthropy," donates all its equipment and services for free.

“Thank goodness for the Shriners,” Richard said. “If they didn’t exist, frankly I don’t know what we’d do. Maybe whittling away at a wooden leg.

“If we ever win the lottery, a huge donation is going to Shriners.”

Chandler’s medical experiences have largely been pain free, except when his stump began to bow as a sixth-grader. Surgery was required and doctors had to break the stump.

“Bringing him home and lifting him to the couch wasn’t much fun,” Richard said. “He’d scream in pain and say ‘Don’t touch me.’ It was hard to know what to do.”

The pain subsided within a week and Chandler was confined to a wheelchair for a month.

“That was definitely painful,” Chandler said. “It was hard.”

Other than that, you won't hear a hint of remorse, regret or “what if” in Chandler. Even when pushed on the point.

Smith has to remove his prosthetictwice each day - once before showeringand once before sleep.

Photo by Louis Lopez

“I guess there are some things I would change,” he said. “But I really don’t know what it would be like to have a right leg. I don’t even know if I’d like it. For me, I’m used to it and I like to push myself.”

Isn’t it hard to talk about?

“It makes me happy that people want to know about my leg,” he said. “I like when they ask. Then I can talk about it and get it out, instead of people just staring at me.”

But hasn’t he ever wondered ‘why me?’ After a very long pause, Chandler said: “I don’t think so.”

Really? No?

“No,” he said.

Even when kids were cruel? Chandler paused, thought again and shook his head again.

What was the cruelest thing a kid or teenager ever said or did?

“Honestly,” he said. “No one has ever been cruel. Not that I know of. … I’ve honestly been treated with nothing but kind words, with love and care. People have always just wanted me to be happy. All I’ve ever had is happiness.”

In an age when bullying and teenage angst appears to be so prevalent, those are refreshing words. But Kay says what goes around, comes around and that Chandler is just one of those kids you can’t help but like and root for. Around the city’s prominent mall, his parents say, kids constantly yell out Chandler's name.

And it has nothing to do with him missing a limb.

“He’s quiet and thoughtful and one of the sweetest kids I know,” Kay said. “He never does or says anything mean to anyone.

“I feel like he goes by the phase 'If you don’t have something nice to say, don’t say it at all.'"{PAGEBREAK}

Diving head first

Smith (middle) listens intently to Chaparral junior varsity coach Tim Mann, a former college goalie himself.

Photo by Louis Lopez

But Chandler is no wallflower. He’s highly competitive and doesn’t mind getting dirty, which is best displayed during 50-50 balls behind the net. Whoever arrives first gains possession and if Chandler gets beat, the goal is empty and the Pumas are vulnerable.

Chandler is already vulnerable and seemingly at a huge disadvantage. He’s clearly not as fast as the other players either. His sprint to the ball is more of an awkward but powerful gallop. He uses all body parts to thrust forward as his iron leg tries to catch up. It doesn’t deter Chandler, Mann said.

“More times than not he beats kids to the ball,” he said. “It’s uncanny. The other kids should definitely get to it first, but Chandler finds a way, partially because others perhaps underestimate him, but mostly because he simply has a heart and will to get there first. He often dives head first.”

He needs that good noggin to get better and learn the game. His lack of speed and mobility, especially getting low to his right side, are major obstacles to overcome, so learning the game intuitively will help compensate, Mann said.

Protecting his lower right, as he does nicely here, willbe a key for Smith in the future.

Photo by Louis Lopez

So too will getting bigger and stronger through weight training – Chandler is only 5-foot-8 and 100 pounds. But judging how intently he listens and soaks up instruction, Smith will get there. His aspirations are to play in college, perhaps at the Division II level.

Mann wouldn’t bet against him.

“He gives me everything,” Mann said. “He listens when I speak. Others who think they are better than they really are don’t always listen. They do what they think they should do. Chandler really listens and he gives me everything he’s got.

“These kids look up to him. He gives them so much encouragement. When he talks, they really listen. They know he’s different and they play better because of it. He brings a lot of unity to the team. They want to protect him so they play harder.”

But there’s definitely no sense of pity for Chandler. Most have been watching and playing side-by-side with him for years in this bedroom community of 100,000 in southwestern Riverside County, a short drive from San Diego and Orange County.

“He’s just such a strong kid – he does everything we do,” said sophomore Anthony Cole, who’s been friends with Chandler since he moved into Temecula just before the third grade. “Nothing can hold him back after everything that has happened in his life. He's on his way.” {PAGEBREAK}

Family Tree

Proud parents Jennifer and Richard Smith have exposed their son to all activities - minus football and diving with sharks.

Photo by Louis Lopez

It helps to have an outgoing and athletic dad like Richard and a nurturing devoted mom like Jennifer.

Richard, a salesman for Spellman High Voltage, competed as a youth in baseball, track and wrestling in the San Diego area. He and Jennifer, a flag team member in high school, fed their son's active nature with sports. They recognized his limitations, but didn’t dissuade him from competing with able-bodied children. One soccer league pushed Chandler to join a special needs league, but Richard and Jennifer declined. Jennifer, in fact, coached the team.

“Anything other than football or scuba diving with sharks we were all for,” Richard said. "We just wanted him to go down a path where he would be happy."

All athletic fields and courts have been his yellow brick road, especially because he was such a fan favorite. Like the first time he hit the ball in a T-Ball game. He was 5.

“I remember everyone going absolutely crazy,” Richard said. “But he had the hardest time getting around the bases. It was like Forrest Gump running for the first time without his braces.”

As Chandler grew older, games requiring speed and jumping became more challenging. He loved basketball and was a good shooter and ballhandler, but lateral movement and getting vertical was next to impossible.

There's little Smith didn't do growing up, including going to the races,as he did here at age 7.

Photo Courtsey of the Smith family

It was a hard reality when he was cut from the team, but that only led him to lacrosse, which was recommended by Cole. Richard, who has stayed active in martial arts and triathlon training, knew nothing about the ball and stick game and figured it wasn’t a match.

“I thought it was a lot of running and cutting,” he said. “When they said he’d play goalie, I thought OK. But then I felt how hard those balls are and thought I wouldn’t want do that. Those things hurt.”

But watching Chandler compete has helped take away some of the family hurt.

Jennifer’s father was recently diagnosed with Stage 4 throat cancer. She also has a bulging disc in her back that needs surgery. In all the years her son has competed, she’s missed attending only once and that was to watch daughter Courtney perform in dance.

“I love watching him play,” she said. “All the boys on the team are amazing. They always have wonderful things to say about him. They’re always encouraging. They just treat him like a normal boy. A normal boy who is missing a leg.”{PAGEBREAK}

No Limitations

Smith played golf and baseball previously, so he knows how to wield a stick. He also can ring up 15 military pull-ups without a problem.

Photo by Louis Lopez

Rick Riley, founder and owner of Specialty Prosthetic Systems in Carson City, Nev., said Chandler’s healthy attitude and active life isn’t surprising.

Socially and technologically, society has advanced dramatically Riley said since he lost his right leg just below the knee 38 years ago in a motorcycle accident. Riley is a prosthetic industry activist, product innovator and president of a million-dollar company. Six of the seven people who work for his company are amputees and have worn prosthetics for a combined 175 years.

Among many physical feats, Riley has bicycled 2,500 kilometers in the Alps, climbed Mt. Rainier and represented the U.S. in skiing at the Disabled Olympics and Able Bodied World Masters Championships in Seefield, Australia. He was also part of the first disabled competition in the U.S. Biathlon Championships in 1989.

Over the years, Riley has watched the number of amputees participating in organized competitive sports climb to now more than 5,000. Almost 20 percent of those are at the prep level.

“We now definitely live in an enlightened society (concerning amputees),” Riley said. “When I lost my leg in 1974, parents of children would pull their kids aside and say ‘Don’t bother that gentlemen,’ Today, kids come up and just say ‘Cool. You’re like the bionic man.’

“Today there is no social sigma.”

And there is no shortage of heroes for Chandler and others to follow. Among the many:

*

Jim Abbott, 44, was born without a right hand. He played 10 Major League seasons and won 89 games for four different teams and threw a no-hitter in 1993.

Smith and the Pumas (7-3-1) close their

season Saturday in the Nathan Powell tourney.

Photo by Louis Lopez

*

Alex Fourie, 16, was born without a right arm. But he can drive a golf ball 270 yards for Shades Mountain Christian (Hoover, Ala.). He’s co-captain of the golf and soccer teams at Shades Mountain Christian and kicker on the football team.

*

Jeff Kiba, 27, was born without a fibula. He broke the Skyline (Sammamish, Wash.) high jump record his first meet (6-2) and went on to set a Paralympic world record jump of 6-11 in 2007.

*

Sarah Reinertsen, 36, is an above-the-knee amputee who was also born with proximal femoral focal deficiency. She was the first to complete an Ironman Triathlon (2005) and holds the world record for above-the-knee amputee in the marathon (5:27) and half marathon (2:12).

*

Anthony Robles, 23, was born with one leg. He won the 2010-11 NCAA 125-pound national wrestling championship for Arizona State and finished 36-0. Robles won two state titles at Mesa (Ariz.), was 129-15 in his prep career and 96-0 during his final two seasons.

“In my experience over the years, the only limitations of the amputee is whatever they place upon themselves,” Riley said.

And at this point, Chandler, or his family, has placed few, if any.

“I don’t think my son tries harder because he has a disability or he’s trying to prove anything,” Richard said. “He tries hard just because he wants to get better at something.”

Said Mann: “He just wants to play. He wants to come out and have a good time and get better. He doesn’t see his own limitations and no one else sees it either. It’s very encouraging at every level.”

Said Jennifer: “He doesn’t let anything stop him. That’s what I love about him.”

Said Chandler: “There’s no limits. I have a mindset that I can do anything.”

Email senior writer and columnist Mitch Stephens at mstephens@maxpreps.com and follow him on Twitter @MitchMashMax.