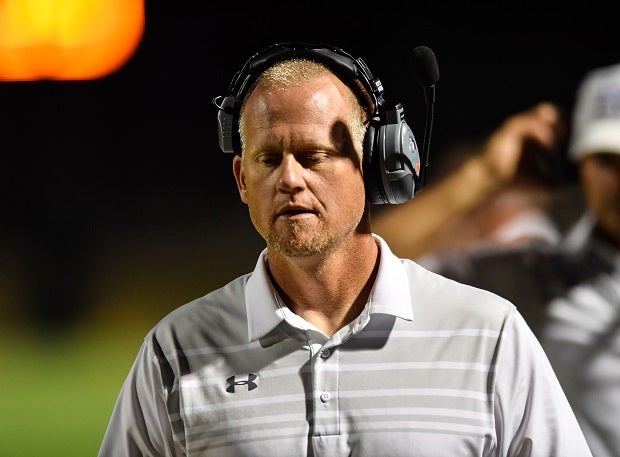

Mansfield coach Dan Maberry has battled cancer and fought to get back on the sidelines. MaxPreps is hoping to make a difference in the battle against this dreaded disease with its Touchdowns Against Cancer campaign. Teaming with St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, MaxPreps is raising money to help fund cancer research.

File photo by Gordon DeLoach

Dan Maberry first realized something was wrong when the feeling he normally got after working out wasn't going away.

"My muscles were extremely fatigued. When I would walk around, it would feel like my legs had lactic acid built up in them," said Maberry, who is in his third year as head football coach at

Mansfield (Texas). "Also, I would get winded just doing small task. I also became very pale and that's when I went to the doctor for a test."

A trip to the doctor last January confirmed his worst fears. Maberry, 45, had stage 4 lymphoma. He let his team know within a couple days of his diagnosis.

"I received the news on a Friday. ... On Monday, I addressed the team and told them my situation and told them I was going to fight," he said. "We kind of had a pep rally. I wanted to be positive when I talked to them and they responded in a positive way. We actually had a great workout that day in offseason."

For

Glendale (Springfield, Mo.) football coach Mike Mauk, the only indication he had that anything was wrong was that he was having more difficulty going to the bathroom. He found out about his colorectal cancer in June 2015. He waited several weeks before letting his team know.

"It was very low key," he said. "I just wanted them to be aware of where I was going to be the week I missed practice."

Maberry's and Mauk's stories are similar to the stories of many high

school coaches throughout the country who battle cancer. The sport they

coach is very much a part of the healing process, whether it's the

support of the players and the community or the motivation to get

back on the sidelines.

To that end, the relationship between

football and cancer has a long history, but not all of the stories are

happy ones. For every inspirational story, like those belonging to

Maberry and Mauk, there are other stories filled with sorrow. Sometimes, however, even the sad tales can lead to something great and even

life-changing.

Maberry took over as Mansfield coach in 2016 after spending time as an assistant coach. He led the team to records of 10-3 and 11-2 before learning of his diagnosis. His battle with cancer has had a surprising effect on his life.

"I despise cancer, but I also view it as a blessing in my life," he said. "I was truly overwhelmed by the support of the community and the coaching fraternity. God used them to pick me up time and time again. The amount of support I received was unbelievable. I saw the goodness in people and how they can love on you! I also enjoy every moment so much more! I had the best summer ever with my family because I appreciate them so much more now."

Mike Mauk, Glendale

File photo by Richey Miller

Mauk spent the greater part of his coaching career at Kenton High School, just an hour's drive from Canton, Ohio, the birthplace of professional football.

Mauk has carved out a 40-year coaching career as an architect of one of the most potent passing attacks in the nation. The national high school record book is filled with names of quarterbacks who played for Mauk. In fact three of the top four all-time leaders in passing yardage played for Mauk. No. 4 is Alex Huston of Glendale with 16,566 yards while No. 1 and 2 are Mauk's own sons, Maty with 18,932 yards and Ben with 17,364 yards.

Both Ben and Maty, along with Mike Mauk's wife, were by his side as he battled his cancer.

"The most difficult part for me was seeing my wife and children struggling with what I was going through," said Mauk. "I had never really been sick before and for them to see me battling for my life was the most difficult thing for me. I did my best to stay strong and confident."

Mauk's faith in God ultimately helped get him through the process.

"I just remember asking God to give me the strength to make it through the treatments. I decided I wasn't going to give up and I was going to fight hard to get my strength back," he said. "I believe God answered my prayer and the prayers of many people who were praying for me. For those prayers, I am forever grateful."

* * *

MaxPreps is hoping to make a difference in the battle against this dreaded disease with its Touchdowns Against Cancer campaign. Teaming with St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, MaxPreps is raising money to help fund cancer research.

"Touchdowns Against Cancer is MaxPreps most important program. It provides us an opportunity to use our platform to unite high school football teams across the country to help fight pediatric cancer," said MaxPreps founder and president Andy Beal. "Of course, we wanted to pick the best beneficiary of the funds we help to raise, and St. Jude was an obvious choice. They do world class research on pediatric cancer, provide amazing care for the kids they treat, and they never turn away a patient for lack of funds to pay for treatment."

* * *

Amos Muzyad Yakhoob Kairuz grew up in Toledo when it was the center of the high school football world. The Toledo Public City League was one of the best prep football circuits in the nation. It featured Toledo Scott, the No. 1 team in the nation in 1922 and 1923 and Toledo Waite, which was No. 1 in 1924 and 1932.

But Amos was more interested in theater and eventually made his way to Detroit where he worked in radio. Struggling to make it in the entertainment industry, he made a vow to St. Jude Thaddeus, the patron saint of hopeless causes, "show me my way in life and I will build you a shrine," he said, according to the St. Jude Children's Research Hospital website.

Nearly 20 years later, Amos had made a name for himself in television, only by then he'd changed his name to Danny Thomas. He starred in

Make Room for Daddy, which had an 11-year run starting in 1953. By the mid-1950s it was time to make good on his vow. He reportedly went around the country raising money and he eventually built the St. Jude's Children Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn.

One of the people who helped Thomas raise money was his fellow Lebanese friend Joe Robbie, according to the Palm Beach Post. Years later when Robbie was trying to raise money for a business enterprise, he visited Thomas's St. Jude donors and even got Thomas to pitch in himself. That's how Danny Thomas became part owner of the expansion Miami Dolphins in 1965.

* * *

While Thomas quickly sold his interest in the Dolphins, Miami went on to play a role in the life of a young man from Minnesota. Mike Grant, the son of Minnesota Vikings coach Bud Grant, saw his father's team lose to Don Shula and the Dolphins in Super Bowl VIII.

Flash forward 45 years and Mike Grant has put together an outstanding career as a high school football coach at

Eden Prairie (Minn.). With 333 career wins, he has the third-highest total of wins in the state. His 11 state championships are the most in state history. So revered as a coach, Grant even won, perhaps ironically considering his father's coaching history, the Don Shula Award, which recognizes the top high school coaches in the country.

But like Mauk and Maberry, Grant and his team have been affected by cancer. Not only did Grant lose longtime assistant coach Lyle Schuette to pancreatic cancer in November 2017, but another longtime assistant Steve Born is battling multiple myeloma, cancer of the blood cells.

Over the summer, Grant's brother, Bruce, a record-setting quarterback at Minnesota Duluth college in the 1980s, succumbed to brain cancer.

"Is something going on — I mean like is there more cancer or are we just getting older?" Mike Grant said during an interview with KARE 11 last year. "But then when it hits home, right when you have the personal people that you love, yeah, it's a tough fall."

In September 2017, Eden Prairie had a night for the players to honor both Schuette and Born.

"If we're about lessons for kids, then this is a great lesson for kids. Honor those people that have been part of your program or your family — I think it's a great lesson for them to see how much we care as coaches — for each other," said Grant.

* * *

Approximately 14 professional and college football players have died during their playing days due to cancer. Perhaps the most celebrated victim was Heisman Trophy winner Ernie Davis of Syracuse, who was the first pick in the NFL draft but never played in the league after being diagnosed with leukemia in the summer of 1962. He died in 1963.

Brian Piccolo played several years in the NFL with the Chicago Bears, but was diagnosed with

germ cell testicular cancer at age 26. He died in 1970. A graduate of Central Catholic of Fort Lauderdale (now St. Thomas Aquinas), the school's stadium is named in his honor.

Joe Roth played his senior season at Cal-Berkeley knowing that he was dying of melanoma. An All-American, Roth finished ninth in the Heisman Trophy voting that year. He died just three months after the season ended. His number 12 is the only jersey ever retired by the Bears.

But perhaps no football player has had more impact on cancer and the work toward its cure than Freddie Joe Steinmark.

An undersized running back from Wheat Ridge, Colo., Steinmark received his only college scholarship offer from the University of Texas. There, Steinmark developed into an all-conference safety and was a valuable member of the 1969 Longhorns' national championship team.

However, Steinmark never played in the Cotton Bowl against Notre Dame, a game Texas won 21-17 on New Year's Day 1970 to win the national title. Three weeks earlier, after playing in a 15-14 win over Arkansas that was deemed the "Game of the Century", Steinmark went to the doctor due to pain in his leg.

The diagnosis was osteogenic sarcoma. He had his leg amputated at the hip on Dec. 12, just six days after playing against Arkansas.

On Jan. 1, Steinmark was standing with crutches on the sideline rooting on the Longhorns. According to a story about Steinmark in Sports Illustrated in 2015, his show of courage reportedly inspired President Richard Nixon, who had met Steinmark in the locker room following the Arkansas game. A year later, Nixon signed the National Cancer Act as part of his "War on Cancer."

Funding for cancer research soared as a result of the Act as it called for $1.9 billion ($9 billion in today's dollars) to be spent on cancer research.

* * *

Steinmark did not benefit from the Act he helped inspire as he died June 6, 1971 — about six months before the passage of the bill.

But the Act likely helped those such as Mauk and Maberry, who have seen their cancer go into remission.

It also likely helped Shon Coleman, an offensive tackle for the San Francisco 49ers. As an incoming freshman at Auburn, the Memphis, Tenn., native was diagnosed with leukemia.

Coleman spent two years at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital in his hometown to begin treatment. After two years, he returned to Auburn and was eventually drafted by the Cleveland Browns in 2016. He was traded to the 49ers in August 2018.

Coleman's alma mater, Olive Branch, has three Touchdowns Against Cancer games this year, including a final one against Lewisburg on Sept. 28.

Glendale (Springfield, Mo.), Mauk's team, has four Touchdowns Against Cancer games this season including a final game against Kickapoo on Sept. 28.

Returning to coaching was a motivating factor for Mauk, who has won 244 games during his tenure at Kenton and Glendale.

"I only missed a week and I did not miss the game after my surgery. My surgery was in the middle of our season," he said. "My recovery from surgery came quickly because I had to get back to what I love doing and that was coaching."

"There is tremendous joy for me being a coach," he added. "It is all I have ever done in my adult lifetime. I love working with all of the players I am privileged to coach. We have outstanding assistant coaches and I get to spend quality time with two of my sons doing together what has been a big part of their lives."

Maberry's Mansfield team concludes its four-game Touchdowns Against Cancer run on Sept. 28 as well, taking on South Grand Prairie.

Maberry feels that coaching was a motivating factor in getting him back on the sideline.

"I truly believe that God put me in this role for a reason. I am supposed to be a football coach," he said. "God allowed me to see the bigger picture so I could see how to use this event in my coaching and everyday life. I am a better coach because of my experience."