John Zisa is a staple in the northern New Jersey football coaching community. It's not because people have sympathy for him. It's because he is a legit football coach.

Photo by Brian Falzarano

Under a nearly cloudless blanket of blue sky behind

Westwood (Washington Township, N.J.), John Zisa is right where he belongs. With dozens of teenage eyes and ears fixated on the venerable assistant coach, his arms flail, his voice rising to a raspy growl as he explains the intricacies of defensive line play.

This scene has played across stretches of turf along Zisa's lengthy coaching calendar under his intensely watchful eyes, a rite of pigskin passage as normal here and from coast to coast as the clash and crunch of pads, the inevitability of a victor and loser emerging from every play, every game.

Just as a pair of his pupils line up, he looks down, directs his left arm toward a lever, and wheels himself away from the action.

From doctors telling his parents and brother he would survive only three years following a most unfortunate swimming accident days before his senior year would have started at Fair Lawn High School, turning a potential collegiate prospect into a quadriplegic, Zisa has already defied the odds by becoming, let alone flourishing, as a high school football offensive and defensive line coach.

Strip away the wheelchair, however, and he is a testament to how faith, a remarkably large and loyal circle of friends and sheer resolve have helped him survive while crafting a career as one of northern New Jersey's most renowned line coaches.

"The accident doesn't define me," Zisa, 48, said defiantly. "What I do and my accomplishments as a coach define me."

Twenty-five years later, he continues to inspire awe.

"He really puts things into perspective what you're trying to teach the kids about mental toughness," said Westwood head coach Vito Campanile, also a close friend of Zisa's. "That guy has had every excuse under the sun to crawl away and do nothing. And he hasn't."

A life-altering dive

Zisa's legacy has earned him constant attention from his players.

Photo by Brian Falzarano

The memory inspires a burst of laughter. Mike Campanile cannot help but laugh when recalling the time Zisa ripped a cast off the broken arm he suffered a week earlier, just to play for the coach's vaunted Fair Lawn recreation team of the late 1970s.

A couple of years later, Zisa cracked his hometown high school's starting lineup as a sinewy 147-pound offensive guard his sophomore season, more than holding his own against blue-chippers from the Bergen Catholics and St. Joseph's Regionals of the rugged former Northern New Jersey Interscholastic League.

"He was just incredible," said Campanile, former head coach at Paterson Catholic and Paramus Catholic, and patriarch of one of New Jersey's most expansive coaching trees. "He would never give up, ever."

Before his senior year, letters starting arriving from Division II schools. Zisa had set his sights further south, inspiring the country music fan during every set of sprints at Goffle Brook Park just across the border in Hawthorne.

On Aug. 27, 1980, days before the start of his senior year, Zisa dove into his friend's pool in Fair Lawn.

His head collided with the liner.

The liner gave.

His head did not.

"I've taken harder hits," he thought while floating underwater. After describing the initial impact as akin to being electrocuted, his sinewy limbs went limp.

Zisa stayed underwater about 90 seconds, keeping his mouth closed because swallowing water surely would have meant drowning. All he saw was a sun ray breaking through the water from the west and one of his closest friends, Chris Finn, yelling to him.

"I'm thinking he's goofing around," Finn said. "But I'm not seeing him move too much."

Realizing this was no teenage prank, Finn dove to the bottom of the pool, some 12 feet down, scooped up Zisa and delivered him to the surface.

"It just didn't seem like there was this damage that was done because there wasn't any pain, he wasn't screaming, he wasn't crying, none of that," Finn said.

After hoping against hope that Finn could straighten out his already straightened legs, police and paramedics arrived. Before undergoing surgery four days later, he endured countless tests at Valley Hospital in nearby Ridgewood, to Bellevue Hospital Center in Manhattan, and then eventually over to nearby New York University.

All offered the same grim diagnosis: Shattered C-4 and C-5 vertebrae — "I obliterated them," Zisa said — that would leave him wheelchair-bound for however much longer his future extended. A future, doctors told his parents and brother, would only extend, best-case scenario, another three years because of the health concerns that stem from spinal cord injuries.

Zisa never knew this until years later, just before his mother passed away in 2007. Not that it would have deterred someone with the stubborn spirit of a 147-pound sophomore starting at guard just two years earlier.

"My mindset was still, 'I'm going to shake it off,'" Zisa said.

The road to recovery - and the sideline

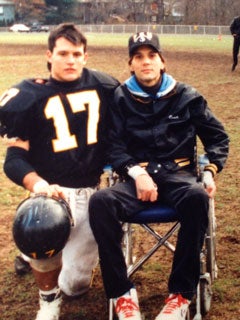

Zisa in his earlier years.

Courtesy photo

Over the next nine months, Zisa wore a halo while learning to live his 17-year-old life anew. Following a 12-hour surgery, doctors stabilized his health at NYU over the next two months before transferring him over to Kessler Institute for Rehabilitation — which later treated spinal-cord patients Christopher Reeve and, later, Rutgers' Eric LeGrand — in West Orange, N.J.

"This injury here, the way I put it, is relentlessly merciless. It just keeps coming at you and trying to consume you," Zisa said.

If it has consumed his body, however, it certainly has not consumed his soul.

Across the next seven years, Zisa developed breathing, vocal and muscular dexterity in his arms that has enabled him to maintain his health into the here and now. Although his hands are permanently balled into soft fists, the rest of his wiry limbs allow him to aptly make a point, on or off the field.

"If you want to survive this," Zisa said, "you better think outside the box."

One afternoon in the summer of 1988, a young assistant coach named Richie Graff picked up his lifelong friend and parked Zisa's wheelchair on the sideline at Paterson Catholic, where Campanile had just become head coach. After offering a few suggestions about footwork and technique on the ride home, Graff and Campanile convinced their friend to consider starting a new future in football.

"I happened to be coaching and I knew that he always loved the sport," Graff said. "It was no great shakes to bring my friend to a practice."

Added Campanile: "Once I saw how he was, I said, 'This kid is born for this.'"

"A legit football coach"

Football coaches and community members often pitch in to help Zisa pay his bills.

Photo by Brian Falzarano

Rutgers defensive line coach Jim Panagos recently spent a few hours at Zisa's home in Fair Lawn, N.J.,

discussing the finer points of playing in the trenches. Dozens of other coaches have done the same through the years.

Of course, there were those who cast judging glances and aspersions upon seeing a coach in a wheelchair during the early days of Zisa's coaching career. Case in point: Jersey City's Caven Point in 1991, where Campanile was coaching his first game as sideline boss at Paramus Catholic against Ferris High School, with Zisa reprising his role as two-way line coach.

Upon arrival, Campanile and his staff encountered a man from the Jersey City recreation department impeding his team's path after seeing Zisa.

"He said, 'What are you doing with that cripple?'" Campanile recalled.

Arguing ensued, but the recreation department member was unrelenting.

"He said, 'No … you can't have cripples on the field. Insurance won't cover him,'" Campanile said.

The next scene underscored the loyalty and camaraderie Zisa has inspired across his 48 years: A close friend of Campanile's and Zisa's decked the man from the recreation department.

Zisa coached from the sideline that afternoon.

"We lost the damn game," Campanile said, "but everything went down good."

At Paramus Catholic, the Paladins defeated mighty St. Joseph Regional for the first time ever in 1992, just days after Zisa's father, Bill, died of a heart attack. They dedicated the game to their beloved coach and his family.

From Paterson Catholic and Paramus Catholic, Zisa continued coaching at Elmwood Park, Fair Lawn, Rutherford two separate times between 2001 and 2009, and now the past three seasons at Westwood. Always in demand, he has only coached alongside fellow members of the Campanile coaching tree, an example of inspiration at each stop along his path who has helped each program evolve on and off the field.

"This isn't about sympathy," Graff said. "This is about a legit football coach."

Without digging his cleats or knuckles into the turf, Zisa skillfully explains in ways coaches without four fully functioning limbs cannot. During a drill called "Wrong Arm" which simulates a trap play, Zisa guides a Westwood player, slowly, through how to peek his head around an offensive lineman's rear end, how to rip his inside arm, maneuver his feet and blast an oncoming blocker.

"You're not going to meet a more dedicated, knowledgeable guy," said Gerard Jordan, a Westwood assistant coach and close friend. "Even if he was out of the chair, he would still be the same coach."

"His kids become like robots," said Roger Kotlarz, Zisa's defensive coordinator at Rutherford in the early 2000s. "And that's good. Because he just focuses on the same things, the fundamentals, so well."

Additional testimony comes from Scott Wisniewski, a former standout under Zisa at Elmwood Park and current head coach at his alma mater: "For someone that can't physically do it, that just shows you how good of a teacher he is."

Like Wisniewski, Westwood senior Connor Carlstrom benefited from Zisa's expertise. He emerged as an All-League defensive end in 2011 after converting from linebacker.

"I just ended up learning everything about the defensive line (from him)," Carlstrom said.

"Blessed that I can give back"

Zisa with Vito Campanile.

Courtesy photo

From the days when Graff brought his good friend to Paterson Catholic practices, Zisa's fellow coaches and friends enjoy taking him to and from practice. After film review following the last of a day of double-session practices, Vito Campanile, one of Mike Campanile's four coaching sons, and his younger brother and assistant coach, Nick, wheel Zisa into his specially equipped mini-van and drive him back home.

From Fair Lawn to the field and back, they talk life. Football. Family. All of the coaches fortunate enough to enjoy this journey with Zisa become extended family.

These days, Zisa lives alone in his mother's old home. Caretakers assist him morning and night, but getting ready for a day out is a lengthy process. Even more so since his primary caretaker, Connie Zisa, died Christmas week 2007 — a woman several friends described as a "saint" for her ceaseless devotion to her son that included helping him live day-to-day, as well as willingly frying up pepper-and-egg sandwiches during late-night coaching meetings at Zisa house.

"How could you not want to do anything for him?" asks Westwood assistant coach John Frick.

Zisa works long hours, but is a volunteer coach because accepting payment would jeopardize the monthly Medicaid check that represents his sole income.

This is where the kindness that comes from Zisa's kinship with a large circle of friends he says he can count on both hands and feet comes into play. They bring him meals, uncap water bottles and wait while he takes a swig, or feed him pizza while poring over game film; when not chewing, Zisa takes detailed notes simply by putting a pen in his mouth.

"He's our friend," says John DePalma, who coached with Zisa at Paramus Catholic, Elmwood Park and Rutherford. "We just like being around him. Everybody just likes being around him."

Says Graff: "For whatever we give, he's given back double in everything he's given to us."

This explains the growth of The Beefsteak Club, organized by DePalma and Graff and held every other June. The venues keep growing, with 275 attending the last get-together in 2011. All funds raised help defray Zisa's living expenses, including wheelchair and van maintenance and upgrades.

"We didn't have to make too many phone calls to get people to come. People were calling us," DePalma said.

Most of Zisa's former players become close friends. Only some have their pictures hanging in the hallowed "Wall of Warriors" inside his home. Wisniewski is one of them. So is Sean Ryan, a star quarterback when Zisa first started at Rutherford who later coached his inspiration at his alma mater.

"He's been a mentor to me," Ryan said. "He's someone I've always looked up to as far as being a leader. When things aren't going well, you have to get tough and be a leader."

Leadership. Inspiration. Perseverance. This is a life's work well done.

Under a blanket of blue sky behind Westwood High School, John Zisa is right where he belongs.

"It gives me such great satisfaction," Zisa said. "I'm getting paid more than what money's worth.

"I feel that I'm productive. Even though I'm in this situation, I'm blessed that I can give back."

To assist John financially, the “John Zisa Special Needs Trust” has been established. The non-tax deductible trust is for the sole benefit and best interest of John. It is to enhance the quality of John's life and health, both now and in the future by providing for John's special needs.

Please direct all checks payable to:

Dr. Henry Cooke, Trustee

380 North Midland Ave.

Saddle Brook, NJ 07663

For further information, please call Rich Graff, Trustee, at (973) 616-1765.