Kramer Robertson, then 10, stands on a ladder as his mom Kim Mulkey celebrates her first NCAA title as a head coach. Robertson, now 18 and a senior at Midway (Waco, Texas), and Mulkey have maintained a treasured and loving mother-son relationship.

Courtesy Baylor Communications/Marketing

It's unmistakable, says

Kramer Robertson. Both piercing and soothing. Both constant and timely.

Whether taking a snap from center in the middle of a huge Texas gridiron showdown — aren't all Texas football games huge? — or blasting a pitch deep over the fence in a baseball playoff game, the

Midway (Waco, Texas) star senior athlete can block out all noise, all screams and shouts, all directives and instructions for this — a single voice.

It's not deep or bellowing. It's not traditionally authoritative and certainly not masculine. It's twangy but clear. It's a little pitchy but music to his ears. It's his American Idol, a generation removed.

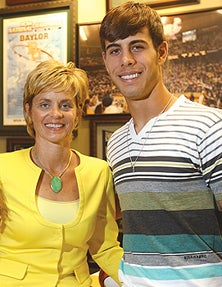

Kim Mulkey and her son Kramer

Robertson this season.

Courtesy of Baylor Communications/Marketing

It's mom.

And she has something to say.

"She definitely has a distinctive voice," said Robertson, the nation's No. 85 senior baseball player and an LSU signee. "Whether it's among 10,000 fans at a football game or 400 at a baseball game, I can always hear it. No matter how much noise, no matter what the situation, I recognize that voice."

As do many around Waco, women's college basketball and the national media.

Robertson's mom is Baylor head coach Kim Mulkey, one of the most accomplished and recognizable figures in the history of women's basketball.

Mulkey is the only person in NCAA history to win national titles as a player, assistant coach and head coach - and we're talking overall, not just the female game.

She was inducted into the Women's Basketball Hall of Fame in 2000 for her many accomplishments as a player, like leading Louisiana Tech to a pair of national titles and helping Team USA to a gold medal in the 1984 Summer Olympics. Her No. 20 was retired at Louisiana Tech and before that at

Hammond (La.), where she piled up a 136-5 record, won four state titles and scored a then-national record 4,075 points.

Kim Mulkey enjoys a post-game

moment with Brittney Griner

following Baylor's 2012 NCAA

championship victory.

Courtesy of Baylor Communications/Marketing

As a coach, she was 430-68 as an assistant and associate head coach at Louisiana Tech before guiding Baylor to a 370-81 mark over 13 seasons, including national crowns in 2005 and 2012.

In 2012, thanks to some help from arguably women basketball's most dominating player Brittney Griner, she led the Bears to the first 40-0 season in NCAA basketball history, men or women, and twice she's been named USBWA National Coach of the Year and four times the Big 12's top coach.

It's a mountain of accomplishment, and even at a squatty 5-foot-4 — she was a feisty, savvy, relentless point guard — Mulkey casts a giant shadow for any child to emerge from.

But Robertson — much like his older sister Makenzie before him who now plays for Mulkey at Baylor — has neither been intimidated nor even attracted to mom's fame. The combination of her strength, smarts and soft heart has prepared him to endure and flourish, much like her teams.

The two have an unmistakable bond and a unique, tender mother and son relationship. Athletic sons and daughters of famous athletic fathers are more common stories told. Athletic sons following the path of a famous mom definitely is something you don't hear about all that often.

Robertson is grateful for the unique journey and said it isn't nearly as rigid as some would think.

"She put a ball in my hand at an early age and watching her all these years has inspired me," Robertson said. "Watching her work so hard, her work ethic and to have good morals, to be a good person and don't let other people change who you are has all rubbed off. I hope they have."

Kramer Robertson picked LSU over

Baylor, Texas A&M and Ole Miss.

Courtesy photo

Mulkey raised Robertson to be confident, be his own person, to keep his head and grades up. To be heard and have a backbone. Living up to expectation and pressure is simply other people's perceptions.

With his mom's blessing, he's been hell-bent to make his own path and name, and by all accounts has done so with a superb three-sport career with a specialty in baseball.

The 5-foot-10, 170-pound shortstop has hit better than .400 each of his four seasons at Midway and landed a scholarship to perennial national power LSU.

"Of course, I'm proud to be known as Kim Mulkey's son," Robertson said. "But I'd like to start making my own legacy and my mom knows and completely supports that. She wants me to be Kramer Robertson and not to just be known as her son."

Said Mulkey: "He'll always be identified as my child and along with that comes pressures and perceptions. It comes with the territory. But Kramer has been prepared for it. He's handled it all gracefully and with a quiet confidence."

Standing tallRobertson grew up in a very athletic household.

His father Randy was a reserve quarterback for the 1973 Louisiana Tech team that won a Division II national title. He's still a big part of Robertson's life and attends virtually all his games. Mulkey and Randy split when Robertson was 11.

Kramer Robertson accounted for more

than 3,600 yards last season while

leading Midway to a 13-1 season.

File photo by Kyle Dantzler

"He taught me how to throw a football," Robertson said. "I couldn't ask for a more caring dad."

Robertson started swinging a wiffle ball bat at 18 months, according to Mulkey, and tried every sport under the sun. More than mom and dad, he followed and tried to live up to Makenzie, who was three years older and starred in basketball, volleyball and softball in high school, earning three state titles at Midway along the way. She was the 2009-10 Girls Super Centex Athlete of the Year.

"It's what the family did and enjoyed," Mulkey said. "We played year-round, around the clock. Kramer did it all. He was born in September and was older than most of the kids. He was always grounded and very mature."

And confident. Extremely so. It's served him well, especially in baseball, a game of failure at the plate.

Midway baseball coach Paul Offill remembered the first time Robertson was in a game-winning situation as a freshman. It was a playoff game, a runner was at third with less than two outs in the eighth inning.

Offill called Robertson down to the third-base coaching box to explain the situation. The infield was pulled in.

"Just hit the ball hard past them or get the ball to the outfield and we win the game," Offill explained to Robertson. "We don't even need a hit."

Robertson looked Offill straight in the eye — just as his mom taught him — and said: "Coach, game's over."

A couple pitches later, Robertson drilled a base hit to right-center field and indeed the game ended. And Offill, in his first season as coach at Midway, threw out his chest.

"I thought to myself, ‘I'm a pretty good coach,'" he said with a laugh.

Offill wasn't worried he was dealing with a prima-donna.

"He is definitely confident, but not nearly cocky," Midway baseball coach Paul Offill said. "It's not arrogance, but just a very calm confidence that when the lights go on he's going to get the job done. We've seen it here on the football field, basketball court and baseball diamond."

Kramer Robertson had a lifetime prep

batting average of .438 heading into

the 2013 season.

Courtesy photo

Robertson started two years of varsity basketball — he was a point guard like his mom — before dropping the sport his senior year to focus on baseball.

As a two-year starting quarterback he led the Panthers to a 25-4 record, losing in the 2011 state 4A championship to Lake Travis 22-7. Midway was 13-0 in the fall before losing in the quarterfinals to eventual finalist Cedar Hill, 49-34.

Robertson threw for more than 3,000 yards and rushed for 600 more his senior year.

"Kramer obviously has a lot of great natural ability," Offill said. "He has impeccable hand-eye coordination. He's a powerful kid. He can dunk a basketball and throw 90 mph. He's one little ball of muscle."

And he stands tall.

Said Mulkey: "I heard one coach say he walks around like he's 6-8 instead of 5-10. I'm sort of proud of that really. I tried to teach him to walk with his head up. It's not an arrogance or cockiness. It's confidence and that's sometimes misunderstood."

That's a topic Mulkey knows all too well.

Verbal, confident women have forever been known as outspoken, unapproachable and many terms worse. Children of famous people automatically get tagged with similar unwarranted, negative tags.

Robertson has learned to live with it and throw a deaf ear to all the critics and cynics of himself and his mother.

"You can't control any of it," Robertson said. "You keep those who are closer to you very close. You don't get too high or too low."

Offill said Mulkey's reputation of being over-bearing – another term for "confident" — is preposterous.

"She is awesome, she really is," he said. "She's one of the best people I've ever been around. Yes, she's a tough coach, but she has a soft heart and is a very sweet lady and is great with her family and son and the entire team.

"Can she push her son and be hard on him? Sure. But she's just or more inclined to wrap her arms around him and love on him."

Kramer Robertson can play either

middle infield spot.

Courtesy photo

And Offill has seen Robertson reciprocate the love right back. In different ways.

Following Baylor's upset loss to Louisville in the NCAA quarterfinals in March, Offill noticed a considerable change in Robertson's demeanor.

"He took it very, very hard," Offill said. "He loves his mom and he knew that devastated her. He was noticeably down."

Said Robertson: "I hate to see my mom hurt in any way. And I felt so bad because there was nothing I could do."

It was quite the opposite feeling, a year ago, when Baylor completed its historic 40-0 season with a win over Notre Dame.

"I think before the clock hit zero I was on the floor hugging my mom," Robertson said. "I'll always be my mom's biggest supporter whether I'm playing at LSU or not. She's always been there for me."

Sugar coatingEven when things aren't going well. Instead of babying her boy, she often offers a dose of tough love. If he has a bad day, Mulkey is going to tell him like it is. Nothing is held back.

Kim Mulkey is know for her spirit

on the sideline.

Courtesy of Baylor Communications/Marketing

Robertson said he fully accepts and loves his mom just as she is. But he's also equipped to bark back – respectfully of course.

"She's a very blunt person," Robertson said. "She's a very intense and competitive person. When I have a bad day, I'm going to hear about it. When I go 4-for-4, she's the first to praise me and hug me.

"But she can't accept failure in baseball like I can. I can still have a good day and go 0-for-3. And we go back and forth about that and she doesn't back down and I don't back down. It's all good."

Mulkey, whose father was an ex-Marine and an exterminator, grew up playing baseball with the boys, never missed a day of school and was a straight-A student.

"I was my father's all-American boy," Mulkey told the

Dallas Morning News in March of 2011. "He was a great dad. If I can be half the mother he was as a father when I was growing up, my kids will be good."

She learned a couple good things along the way.

"Love your kids unconditionally and don't sugar coat things," she said. "Don't kill their spirits of course, let them know you're there for them, but it's better to be brutally honest than to lie and make things easy."

It wasn't easy when Robertson picked LSU over Baylor, Ole Miss and Texas A&M as finalists for his college choice. Mulkey went on the recruiting trips with her son and accepted his choice with a full blessing. Of course, Baylor was her No. 1 choice.

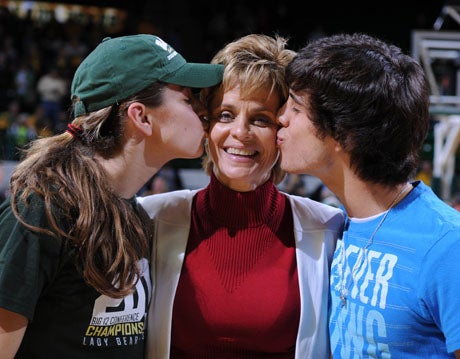

Baylor coach Kim Mulkey is flanked

by her son Kramer Robertson (left)

and daughter Makenzie Robertson.

Courtesy Baylor Communications/Marketing

Robertson believes LSU gives him the best chance to reach his ultimate college goal — win a national championship, something his mom and sister have done. He'll also be close in proximity to extended family there.

"Of course I would love him to be around until he's 22 or 23, to be there close physically. What parent wouldn't?" Mulkey said. "But he has goals he wants to achieve and that's the best place for him. He has a legitimate reason to go, so you let them go. It will be difficult at first, but as soon as the season is over I'll go down and see as many games as possible."

Robertson said it will be difficult for him too. First he and the Panthers are making a state-title run. They continue their best-of-3 series at home against

Bell (Hurst, Texas) on Saturday, the day before Mother's Day.

"It's not the sports stuff I'm going to miss so much, but I'm going to miss the mom stuff," he said. "I won't see her every day. I won't be sitting on the couch and have her come over and rub my back and ask me about my day or scratch the back of my head. All the stuff that moms do.

"I think I'm going to find out pretty quick that I'm definitely a mamma's boy and always will be."

Baylor women's basketball coach Kim Mulkey enjoys a kiss from her son Kramer Robertson (right) and daughter Makenzie following another big victory.

Courtesy Baylor Communications/Marketing